For nearly as long as Georgia Tech has existed, students have come to study civil engineering and improve the world around them.

Civil engineering is one of the oldest engineering disciplines. It was named in contrast to military engineering and created to encompass everything needed to support civilian life. While civil engineering’s core mission remains the same, the field has evolved over time to encompass many specialized subdisciplines, including structural engineering, geotechnical engineering, transportation engineering, environmental engineering, and others.

At Georgia Tech, civil engineering has grown and evolved significantly since the program was established 125 years ago.

What began with one instructor and a handful of students is now one of the top programs in the nation.

With a firm grounding in traditional civil engineering principles, the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering has expanded into an interdisciplinary powerhouse focused on addressing the grand challenges of the 21st century, preserving the planet, and improving the human condition.

Read on to learn about the history of civil engineering at Georgia Tech.

The Jesse W. Mason Building after opening in 1969. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

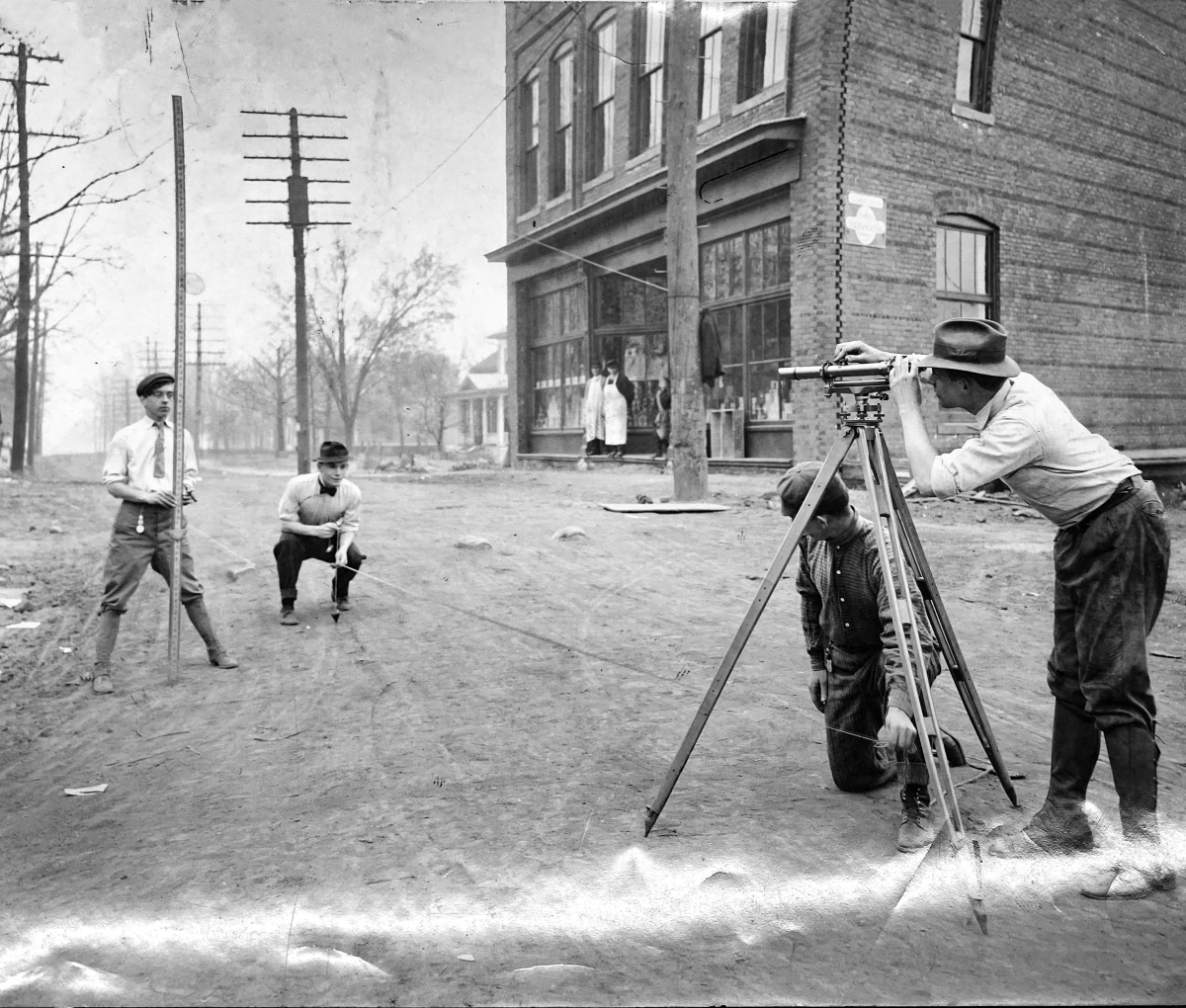

Surveying in 1915 (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

Georgia Tech Faculty of 1900 (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

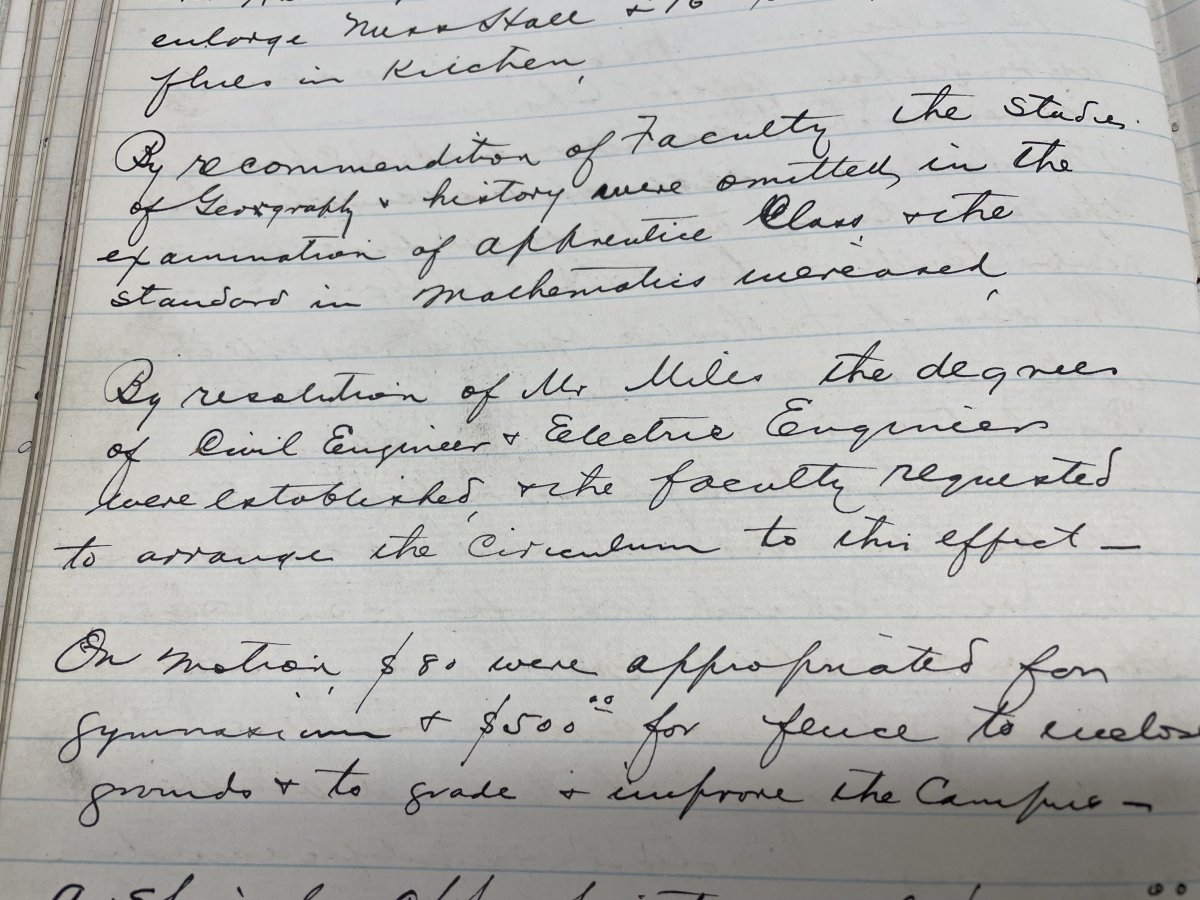

Hand-written meeting minutes from December 1896

1898-1913

When the Georgia School of Technology opened its doors in 1888, mechanical engineering was the only degree offered. Over the next decade, Georgia Tech’s second president, Lyman Hall, worked to expand the school’s offerings with the establishment of two new courses of study: civil engineering and electrical engineering.

Civil engineering seems to have been a special interest for Hall. During his time as a math instructor, he included field work in surveying and mapping in his classes. He also supplemented his teaching salary by conducting surveys in the Atlanta area, according to Engineering the New South, a book on the history of Georgia Tech.

During a Dec. 30, 1896 meeting, Georgia Tech’s Board of Trustees approved the new degrees of civil and electrical engineering, “and the faculty requested to arrange the curriculum to this effect,” according to the hand-written meeting minutes.

Hall became president of Georgia Tech the same year, preventing him from overseeing the new program.

In meeting minutes from June 22, 1898, the Board of Trustees selected Thomas Pettus “T.P.” Branch, a junior professor of mathematics, to lead the civil engineering program.

Branch shaped the development of the civil engineering program during his 28-year Georgia Tech career and served as Tech’s secretary of the faculty until his death in 1923.

The new civil engineering program got off to a sluggish start. Electrical engineering, authorized at the same time as civil engineering; and textile engineering, introduced shortly after, were much more popular.

Between 1901 and 1905, there were 50 graduates in textile engineering, 45 graduates in mechanical engineering, and 33 graduates in electrical engineering. Only seven students graduated in civil engineering during the same period.

In fact, it wasn’t until 1902 that Maryon McDonald Lawrence became the first civil engineering graduate.

The theory for this modest enthusiasm, according to the Engineering the New South, is that there was already a civil engineering program at the University of Georgia.

Perhaps Georgia Tech’s program was born more from Hall’s personal interest in civil engineering than a demand for more trained civil engineers.

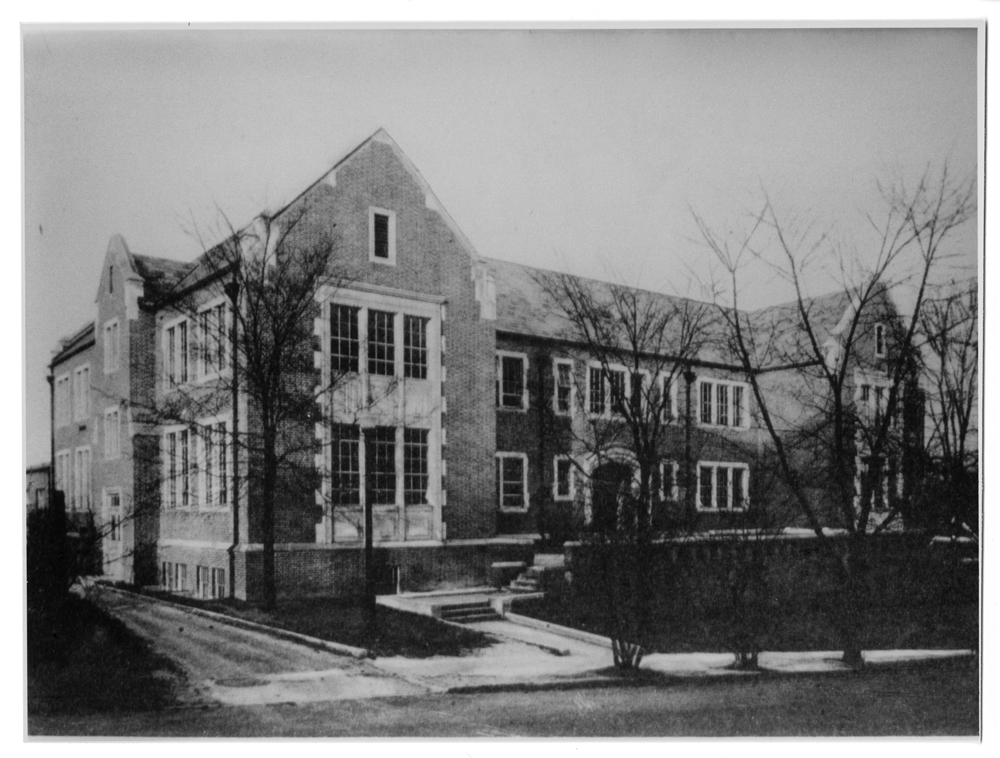

The Old Civil Engineering Building after completion in 1938. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Library)

The civil engineering program expanded in 1914 with the addition of highway engineering.

A pair of Fulton County consulting engineers — Robert Davis Kneale and Franklin C. Snow — were the first department heads. Snow went on to lead both the civil and highway engineering departments following the 1924 death of Branch, the founding head of civil engineering. Because it wasn’t a degree granting program, highway engineering was incorporated under civil engineering as a single department.

Snow remained the head of the civil engineering department until his death in 1945. According to his obituary in the Georgia Tech Alumnus, Snow was responsible for founding the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) student chapter at Georgia Tech, and “he took a deep interest in this work and promoted it with energy.”

During the first half of the 20th century, civil engineering was a scrappy program with resourceful faculty members who found ways to get the equipment they needed.

James Herty Lucas, a civil engineering graduate who served on the faculty from 1915-1960, wrote a brief history of the civil engineering department. In his undated papers, he recalled that much of the department’s surveying equipment came from government surplus.

“There were several transits and levels turned over to the school by the Army after World War I and for years afterward, one of the Army officers would come by each year to check these instruments and make certain that we actually had them,” Lucas wrote. “The equipment is in fairly good condition but it is only by continual cleaning, adjusting and minor repairs that it is kept so.”

During the Great Depression, Lucas secured the donation of a hydraulic compression machine for the civil engineering department in exchange for “extensive work” done for the Public Works Administration (PWA) at no cost. The PWA provided funds and machinists to build this testing machine, which according to Lucas was “the largest capacity of any such machine in this part of the country.”

Created in an effort to help the nation’s economy recover during the Great Depression, the PWA funded construction of more than 34,000 projects between 1933 and 1939, including airports, dams, school buildings, hospitals and roads.

Among the many projects the agency funded during this time was the Civil Engineering Building at Georgia Tech, completed in 1938. Civil engineering shared facilities with other departments during its first 40 years of existence, and this was the department’s first official campus home.

1940s-1950s

In the years following World War II, Georgia Tech’s leadership worked to expand research and graduate education to boost the school’s reputation as a nationally recognized engineering program.

In 1948, the school known up to that point as the Georgia School of Technology was renamed the Georgia Institute of Technology to reflect its growing emphasis on advanced technological and scientific research.

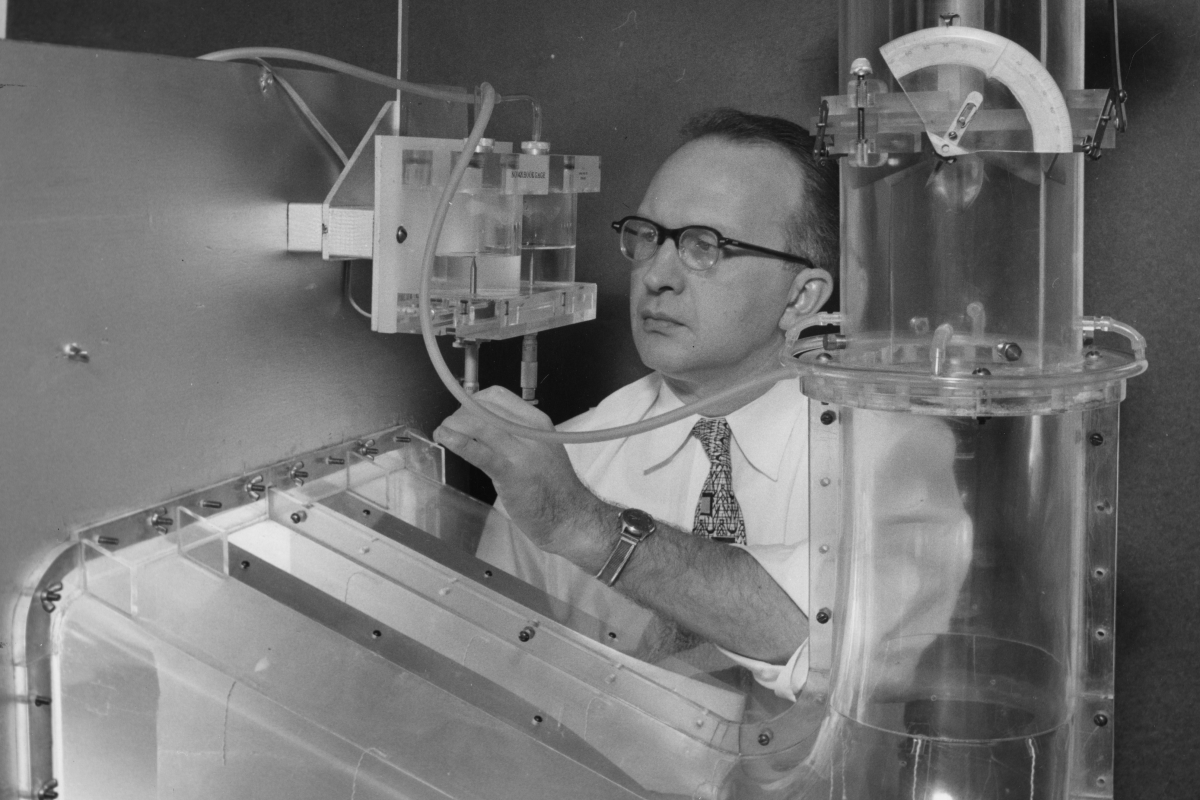

Within civil engineering, this shift coincided with the hiring of new faculty members who brought expertise within the civil engineering subdisciplines of geotechnical and hydraulic engineering. In 1945, Georgia Tech President Blake Van Leer was instrumental in recruiting Carl Edward Kindsvater to campus. Kindsvater would establish a hydraulics laboratory that emphasized hydroelectric power, flood control, and the conservation and regulation of water supplies.

The small lab, located in the basement of the Civil Engineering Building, featured a miniature dam used to simulate hydraulic flow conditions, according to Engineering the New South.

Despite limited resources, Kindsvater was able to get the laboratory up and running within two years, according to a paper on Kindsvater’s legacy co-authored by civil engineering professors emeritus Terry W. Sturm and C. Samuel Martin.

Carl Edward Kindsvater working on an experiment in the hydraulics laboratory. (Photo Courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

Close up of a hydraulics laboratory experiment in 1949 (Photos courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

Dedication of the Chi Epsilon Civil Engineering Honor Society monument in 1945. (Photo Courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

Together with a master craftsman named Homer Bates, Kindsvater designed and built the lab’s equipment, including a glass-walled flume for demonstrations and experiments that is still used today.

Over the next 15 years, Kindsvater produced a body of classic hydraulics research including two papers that received the ASCE’s Norman Medal, a prestigious honor recognizing contributions to engineering science.

In 1947, George Sowers arrived at Georgia Tech and established the geotechnical engineering program in the School of Civil Engineering.

As a graduate student at Harvard, Sowers studied under Karl Terzaghi, the father of geotechnical engineering.

Sowers was recruited for jobs in both industry and academia and ultimately chose to pursue both. He accepted a joint position at Georgia Tech and the engineering and consulting firm of Thomas C. Law.

He excelled in both roles over the next 50 years, rising to the level of Regents Professor and Chairman of the Board at the Law consulting firm. Sowers was a skilled storyteller who pulled from his experiences with forensic engineering to illuminate issues in the classroom or in the field. He is remembered for his boundless energy and enthusiasm, lecturing in class one day and flying across the world to inspect a dam the next. He wrote a textbook, Introductory Soil Mechanics and Foundations, which became standard reading for a generation of civil engineers, according to ASCE’s biography of Sowers.

1960s-1980s

Georgia Tech President Emeritus G. Wayne Clough, CE 64, MS CE 65, was a civil engineering student in the early 1960s. The campus atmosphere in those days was tough, Clough said. First year students were warned: Look to your left, look to your right. Only one of you will graduate.

“It was a challenging place. You had to learn to create your own support systems to succeed,” Clough said.

Civil Engineering students and faculty gather for a photo in front of the Jesse W. Mason building in the early 1970s. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

Clough recalls struggling during his first year, seeking to develop the right study habits and working as a cooperative education student as a railroad surveyor.

However, he found the atmosphere in his civil engineering classes to be different. His professors — including Kindsvater, Sowers, and Alec Besich, with whom he went on to conduct research as a graduate student — were invested in his success.

“They really cared about me as a person,” Clough said. “To this day, it’s one of the things that makes civil engineering such a wonderful program.”

In 1969, the School of Civil Engineering moved to a new home as part of a campus expansion. The Jesse W. Mason Building, named for the dean of the College of Engineering, became the new headquarters and was one of several modern buildings constructed along Atlantic Drive.

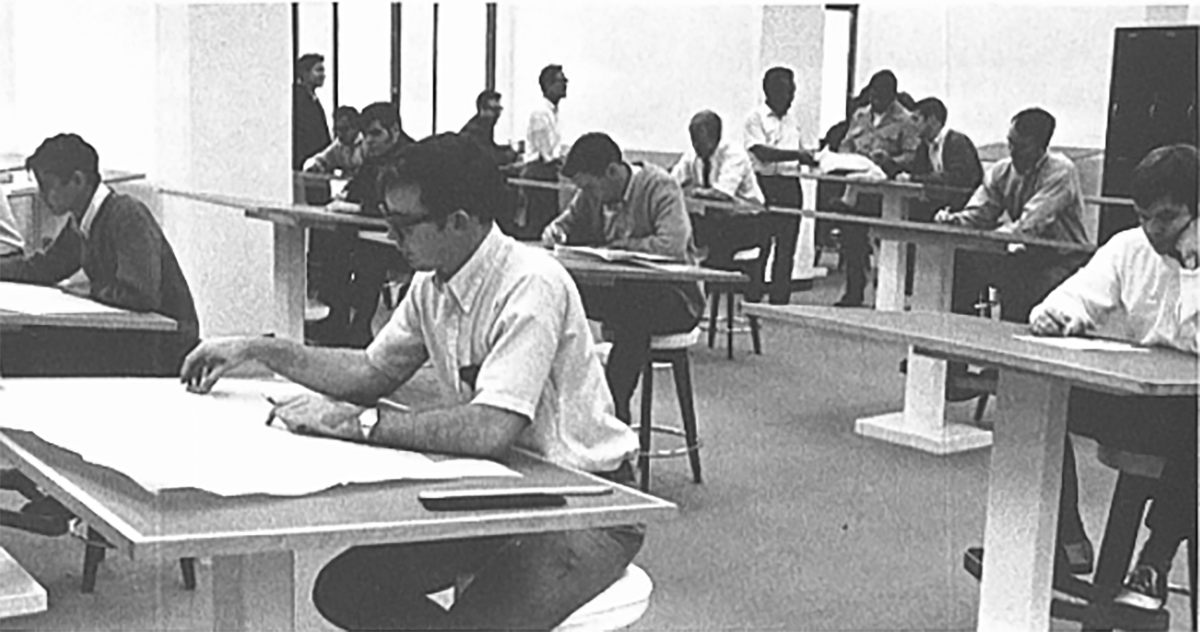

Students working at drafting tables in the Mason Building in 1970. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

With its curving white façade, the five-story, 90,000 square-foot building was a visual departure from the old civil engineering building’s classical red brick, collegiate gothic design. Though it is now home to the School of Economics, the building is still officially known on campus as the Old Civil Engineering Building.

During the 1960s and 70s, the civil engineering subdiscipline of sanitary engineering — now known as environmental engineering — was elevated alongside an emerging environmental consciousness in the United States.

Amid growing concerns about air and water pollution, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established in 1970, and the first Earth Day was celebrated the same year.

In 1972, the sanitary engineering program expanded into the Daniel Environmental Engineering Laboratory. Located next to Bobby Dodd Stadium, the three-story building is still home to many environmental engineering laboratories.

Throughout the 1970s, special attention was given to research related to energy conservation and the environment.

“Government regulations and findings of the Environmental Protection Agency have placed new emphasis on sanitary engineering,” John E. Fitzgerald, then-director of Civil Engineering, wrote in the 1981 Blueprint yearbook.

Charles W. Nelson, CE 70 works on a hands-on project. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

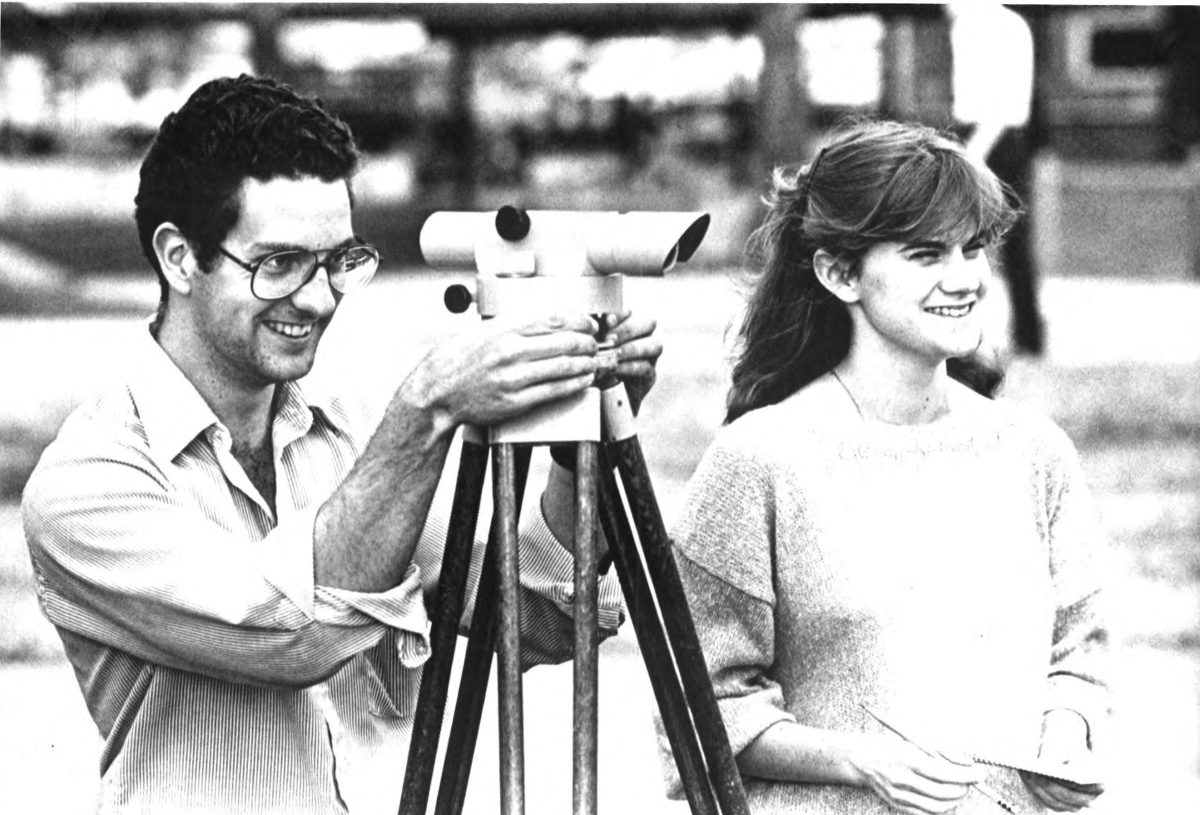

Students using survey equipment in front of the Mason Building. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

Sharon Just, CE 89, working in a lab. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives)

In the 1980s, the School of Civil Engineering began adjusting to the reality that computers were becoming a bigger part of life in every industry. According to the 1984 Blueprint, a major portion of the civil engineering faculty lounge was converted to a student computer terminal facility to help support new courses incorporating the technology.

“Digital computers have become commonplace in business, and the school is compelled to turn out graduates capable of using this technology,” Fitzgerald wrote.

Professor of the Practice Sharon Just, CE 89, recalls the transition to computers was a swift one over the course of her time as a civil engineering student.

“I went to Tech with a typewriter and by the time I graduated, I had a computer,” Just said.

“There was definitely an emphasis on migrating to computers. But surveying and drawing was still a required class. We were drawing to scale, with a pencil and paper.”

Although environmental engineering degrees were offered only at the graduate level then, Just said a formative part of her undergraduate experience was conducting research with environmental engineering Professor Emeritus Michael Saunders.

“He had spent the time to do special research projects,” said Just, who went on to a career in environmental engineering. “He didn’t have to do that – it was one-on-one support to help an undergraduate student be able to do research.”

Just recalled several other times during her education that she had hands-on experiences, like driving to look at bad intersections in Atlanta, learning about water flow in the laboratory, and working in industry as part of the co-op program.

“Georgia Tech did a very good job of providing hands-on, real-world experiences. It continues today, and it’s something you don’t find in other programs,” Just said.

Students adjust equipment for an accurate reading. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Blueprint)

1990s-2000s

Clough went on to become an engineering professor and was serving as provost at the University of Washington when he received a call inviting him to interview for the role of president of Georgia Tech.

At that time, the Institute had a low graduation rate, despite having students with high test scores — a result of the tough dynamic Clough remembered from his time as a student.

“I thought I could do something to change this university for the better,” Clough said. “The culture needed to be changed.”

Clough returned to Atlanta and in 1994 became the first alumnus to serve as president of Georgia Tech. As he began his new role, Clough discovered that the civil engineering faculty had maintained the legacy of student support he remembered from the 1960s.

“I was incredibly pleased when I came back as president and realized that civil engineering was still a program that respected the role of teaching,” Clough said.

In 1991, the school changed its name to the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering. This move reflected a nationwide trend, as environmental engineering became recognized as its own discipline.

Students in the classroom in 1993. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Blueprint)

A photo of the faculty from 1993. (Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech Blueprint)

The School became a leader in engineering education with the addition of the Charles E. Gearing Program in Engineering Communication. Developed by Principal Academic Professional Lisa Rosenstein, it was one of the first in the nation to integrate written, oral, and visual communication skills into the engineering curriculum at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

“Our industry partners and alumni tell us unequivocally about the importance of possessing quality communication skills in engineering practice. This program has been transformational in preparing our students for career success,” said Karen and John Huff School Chair Donald Webster.

On campus, the School’s footprint expanded in 1998 with the completion of the O. Lamar Allen Sustainable Engineering Building. It was constructed using the most up-to-date sustainable materials available at the time. The building contains computer instructional labs and became home to the School’s transportation engineering faculty and research labs.

In 2003, the environmental engineering program branched into the newly completed Ford Environmental Science and Technology Building. The building, one of four in the interdisciplinary Life Sciences and Technology Complex, provided classrooms and research facilities for collaboration between the related fields of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Environmental Biology, Environmental Chemistry, Biomedical Engineering and Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

Though Georgia Tech had offered graduate degrees in environmental engineering — or sanitary engineering as it was formerly known — for decades, it was not until 2006 that the School began to offer a standalone bachelor’s degree in the field.

“The program has been very popular with consistently strong enrollment numbers,” Webster said. “Graduates go on to find employment in industry and government jobs as well as pursue graduate degrees.”

A tour during the renovation of the Mason Building.

Environmental engineering students doing field work during a study abroad trip to Bolivia.

Williams Family Associate Professor Lauren Stewart works with graduate students in the structures lab.

2010-2023

After more than 40 years as the heart of civil engineering on campus, the Mason Building underwent a $12 million renovation in 2013. A series of upgrades brought the building into the modern era, including replacing chalkboards with whiteboards, creating a student commons space, improving wireless connectivity, and reconfiguring the space that once housed the building’s 1960s-era mainframe computer.

The curriculum was updated as well, with an emphasis on global thinking and interdisciplinary learning to tackle the grand challenges of the 21st century. School leadership worked to expand what a civil and environmental engineering curriculum entails in order to graduate holistic engineers prepared for a quickly evolving and increasingly interdisciplinary world.

In 2015, the School introduced the Global Engineering Leadership Minor (GELM). One of three tracks within the Institute’s Leadership Studies Program, the minor was designed to teach students communication and leadership skills, help them gain a deeper understanding of civil and environmental engineering in a global context, and provide opportunities to work, research, or study internationally.

“The courses developed as part of the GELM program formalized training in leadership, which has been an organically developed characteristic of many of our graduates for decades,” Webster said. “The courses are a platform for our faculty to deliver forward-looking material on the important role that civil and environmental engineers play in solving the challenges of the 21st century.”

During this period, the School joined other campus programs to form interdisciplinary graduate degrees. These master’s and PhD programs include Ocean Science and Engineering—a joint program with the schools of Biological Sciences and Earth and Atmospheric Sciences—which combines sciences with ocean technologies to advance research of ocean systems, climate change, coastal developments, and ocean energy. The School also is part of the Computational Science and Engineering graduate program with the Colleges of Computing and Sciences. The program is devoted to the creation, study, and application of computer-based models of natural and engineered systems.

In 2020, the School expanded its global reach, becoming one of five academic units to offer a master’s degree program at Georgia Tech’s campus in Shenzhen, China. Opened during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Master of Science in Environmental Engineering initially served graduate students in China who were unable to travel to Atlanta to study. Now, master’s students in Atlanta and Shenzhen can participate in exchanges to study at both campuses.

And in 2020, the School reached a new milestone. For the first time, more than half of the student body identified as women — a major step toward closing the gender gap in engineering.

Looking Ahead

In 2022, Webster and a team of faculty, staff, students, and alumni completed a strategic planning process to chart a course for the future of the School.

Over the next several years, leaders will work to implement initiatives identified in the plan to strengthen the CEE community, the student experience, research, and service.

“In 2022, we formally launched our new strategic plan with the intention of taking our already excellent school to even greater heights. Combined with the Institute’s capital campaign, Transforming Tomorrow, this is a rare moment to reimagine and elevate everything that we do,” Webster said.

Much has changed over the last 125 years. The drafting tables and ashtrays have been replaced by laptops and sticker-covered water bottles; the mechanical surveying equipment was shelved in favor of software with razor sharp precision. But students and faculty are drawn to civil (and environmental) engineering for the same reasons they always have: a desire to build, to improve, and to preserve the world around them.

Students with Engineers in Action helped build a bridge in an area of West Virginia prone to flooding.

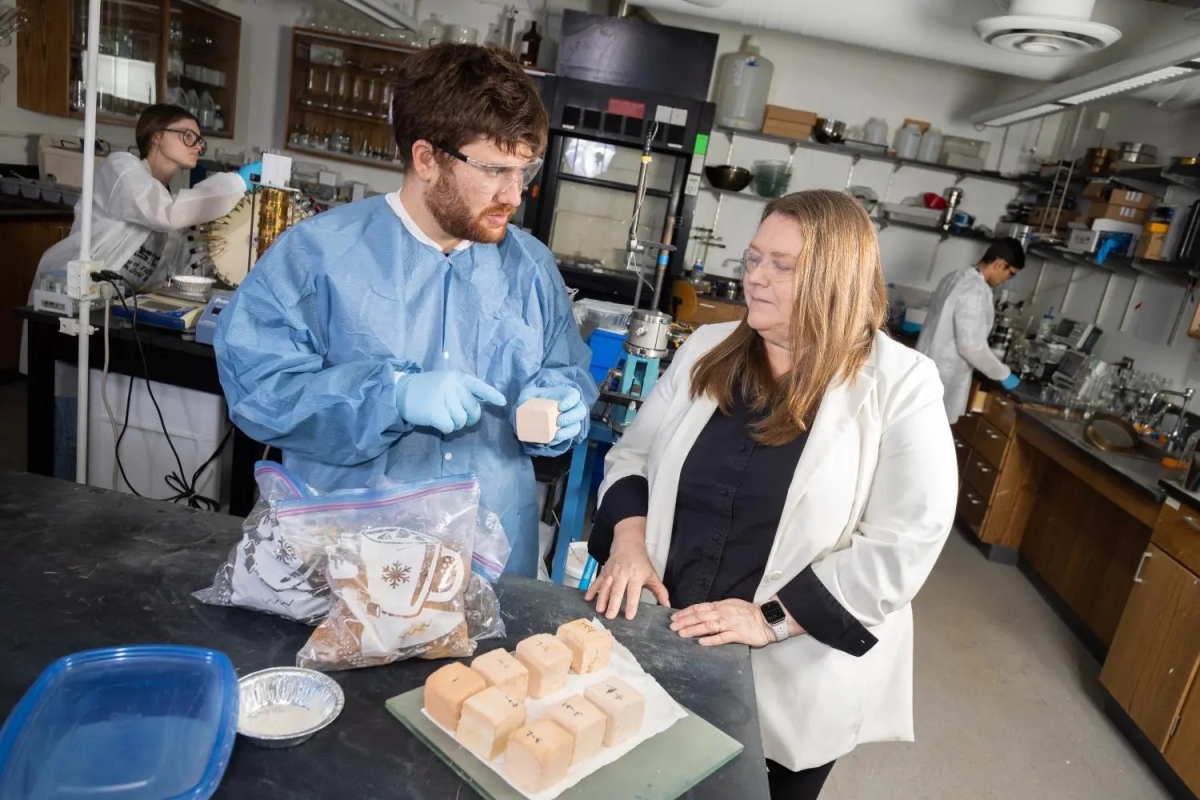

Dwight H. Evans Professor Susan Burns in the lab with students. (Photo by Candler Hobbs)