|

With Hurricane Matthew looming, college football programs throughout the Southeast had to consider the impact of the massive storm on their scheduled games Oct. 8.

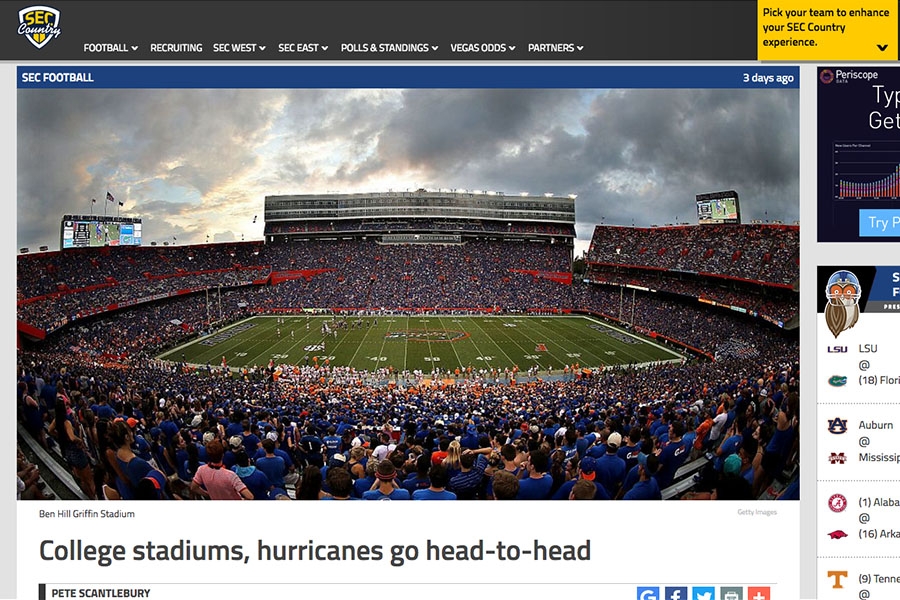

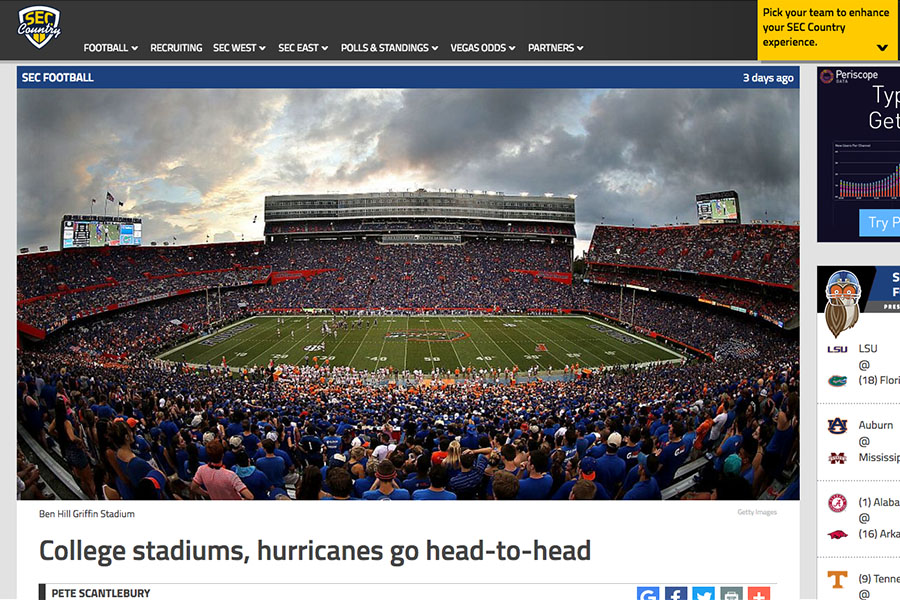

Two games had to be postponed — one indefinitely — prompting the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s SEC Country website to ask what would happen to a stadium in a major hurricane.

“Firstly, wind design makes up one of the many parts of the various hazard loads that we consider when we design structures,” Assistant Professor Lauren Stewart told the site. “The U.S. has adopted building codes, and states such as Florida have additional requirements for high wind conditions. This is what makes the structures in the U.S. so safe, and stadiums would be designed to withstand the type of wind load environment, such as those generated from hurricanes.”

Stewart, a structural engineer in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, said stadiums aren’t designed to come through a strong storm unscathed, but they are designed against failure so that occupants are protected.

“A football analogy is that we design a good offensive line that can take a hit to ensure the QB’s safety,” she said.

Read more from SEC Country’s Pete Scantlebury:

That’s why these structures are often used as safe-shelters during major storms. While water damage can cause flooding if the stadiums are in the path of the storm surge, the stability of the structures, and the fact that they are built to protect the occupants in extreme conditions, means that they can suffer damage without collapsing.

The 2005 Atlantic storm season had the biggest impact on the college football season. The damage to New Orleans and the Superdome caused by Katrina, along with its use as a refugee shelter, forced Tulane to play the entire season on the road. It also caused LSU to move a home game against Arizona State to Tempe, which was announced on Sep. 6, 2005, and played four days later.

Hurricane Rita and Hurricane Wilma, which hit in late September and October of that year, affected the scheduling of more football games. Rita forced Texas A&M to move a home game against Rice up in the schedule, from a Saturday to a Thursday. Wilma’s path through Florida caused Miami and South Florida to postpone games against Georgia Tech and West Virginia, respectively.

Wilma caused minor structural damage to the Miami Orange Bowl, but it was still used as a FEMA relief center. The storm hit Florida on Monday, Oct. 24, 2005, but Miami still hosted North Carolina on Saturday, Oct. 29. The game, however, had to be moved from a night-time kickoff to the afternoon because light towers were damaged.

“… Minor cracking and damage is often acceptable in practice for extreme loading events because you can still get people out of the building (safely),” Stewart wrote. “You may need to repair/replace the structure afterwards, but the people were the priority. Collapse of the structure, on the other hand, is not acceptable because it will endanger the occupants.”