By Jonathan Bowers, Georgia Tech News Center

|

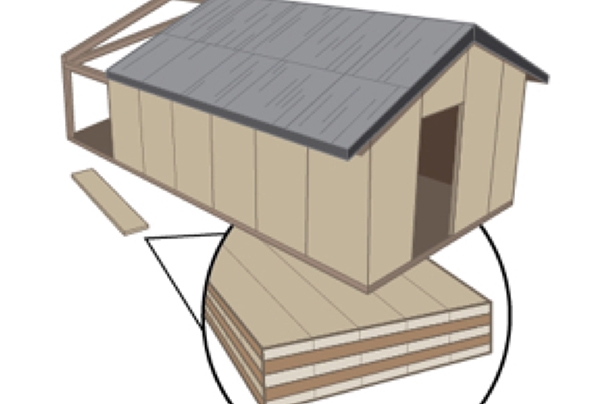

Top: A drawing of potential new temporary barracks for U.S. Army troops. The Army typically uses tents as temporary housing in combat. Georgia Tech is proposing cross-laminated timber as a way to make the barracks more durable than previous building materials and ultimately safer for the troops. Researchers Lauren Stewart and Russell Gentry have received funding from the U.S. Forest Service to create designs for the barracks using wood primarily from the southern United States. Bottom: A stack of cross-laminated timber panels illustrates how the product is made by created three, five, or seven layers of lumber oriented at right angles to one another and then glued together. (Images Courtesy: Lauren Stewart) |

The timber industry, the U.S. Military Academy, U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are teaming with Georgia Tech to design and build better portable housing for overseas troops.

Funded by a grant from the United States Forestry Service (USFS), the project will explore ways to utilize new laminated wood products in the construction of temporary barracks. Lauren Stewart and Russell Gentry saw the products — called cross-laminated timber, or CLT — as an ideal material for the short-term structures while creating a new market for Georgia’s timber industry, the largest in the country.

“With 22 million acres of working forests and a $32 billion economic impact, Georgia is blessed to be the number one forestry state in the nation,” said Andres Villegas, president and CEO of the Georgia Forestry Association. “That’s why we at the Georgia Forestry Association are fully supportive of the research that Georgia Tech is doing with cross-laminated timber through the USDA’s Wood Innovation Grant.

The Forest Service was looking for new uses of the CLT products, a wood panel typically consisting of three, five, or seven layers of lumber oriented at right angles to one another and then glued together.

The United States Department of Defense (DoD) spent more than $150 million over the past five years to design lightweight bunkers, or “b-huts,” for troops, which were an improvement from the tents typically used in combat. Georgia Tech is proposing CLT as a way to make the barracks more durable than previous building materials and ultimately safer for the troops.

The proposed CLT designs use less energy for heating and cooling, and the bunker will be far easier to disassemble and relocate. Both are key attributes for military housing, along with providing adequate protection for troops.

“New markets for wood are critical for the future of our state’s forests, and I can think of no better way to utilize our state’s sustainable timber resources than in a way that benefits both our brave men and women in uniform and our state’s economic vitality,” Villegas said.

This project could be used worldwide, but the research team has proposed it for the southern United States. The wood they’ll use will be mostly indigenous to the South, allowing for less harmful forest management and lower costs. The Georgia Tech team aims to motivate new fabrication facilities and spur economic development in the region.

“This project is a unique opportunity to bring together the USFS, state agencies, military, and academia to advance the state of knowledge of CLT, promote forest health, and develop an application that can enhance troops safety, security, and comfort,” said Stewart, the project’s principal investigator and an assistant professor in the Georgia Tech School of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

CLT has the potential for broader applications, too, as more and more designers look for low-carbon alternatives to traditional construction materials. The research team, along with the Georgia Forestry Foundation and WoodWorks Wood Products Council, hosted a symposium Sept. 26 at Georgia Tech on design and construction using mass timber from the Southeast. They highlighted hotels, mid- and high-rise buildings, and other projects around the country that are using wood products.

Stewart and Gentry, the project’s co-principal investigator, will be assisted by Ph.D. student Kathryn Sanborn, who’s also a major in the U.S. Army. The three-year project’s total cost will be nearly $375,000, including $125,000 that the Institute has contributed as a match. Other significant contributions to the project came from the Army Research Laboratory, West Point and the Army Corps of Engineers.