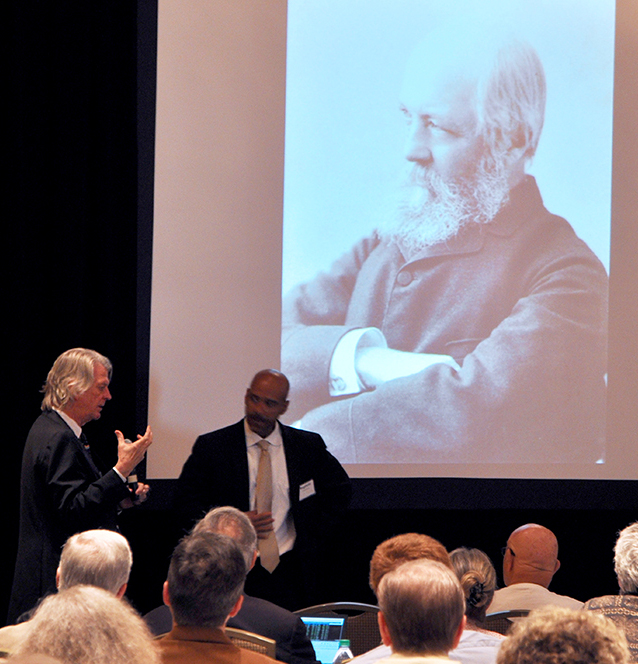

Professor Douglas Allen offers an introduction to the Frederick Law Olmsted Symposium June 2. The symposium was the official beginning of the search for the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering's new Olmsted Chair, an endowed faculty position. (Photos by Jess Hunt.)

Professor Douglas Allen offers an introduction to the Frederick Law Olmsted Symposium June 2. The symposium was the official beginning of the search for the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering's new Olmsted Chair, an endowed faculty position. (Photos by Jess Hunt.)

| • Keynote - The Nature of Olmsted's Genius - Douglas Allen | |

| • Urban River Parkways as Routes to Health: An Olmsted Legacy Reviving from 20th Century Coma - Richard J. Jackson | |

| • Making Places for Thriving People - Howard Frumkin | |

| • Sustainable Infrastructure: The Role of Politics and Governance - Diane E. Davis | |

| • Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.: The Long View of the North American Landscape - Frederick R. Steiner | |

| • Building Places People Love: Integrating Water Management Systems into our Cities, Towns, and Suburbs - Lynn Richards | |

|

• Pleasure Drives and Promenades: The Olmsted Parkway Idea as Inspiration for Today’s Complete Streets - Elizabeth Macdonald |

The School of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) celebrated the father of landscape architecture and began the search for a new endowed faculty member Monday.

The Frederick Law Olmsted Symposium assembled six thought leaders in sustainable urban infrastructure to talk about Olmsted’s work and the concepts he created. It was also the start of a conversation about who can best advance the ideas of sustainability in our cities and suburbs as the new Olmsted Chair in CEE. (More photos from the event, courtesy of Terry Kearns.)

“[Olmsted’s] real genius was in figuring out what was needed to solve a problem and then assembling the people and resources necessary,” said Douglas Allen, professor emeritus in the School of Architecture who opened the symposium. “Along the way, Olmsted attempted to do what any good poet does: he tried to tag poetic language to regular language. So a sewer becomes a parkway.”

That was one of Olmsted’s ideas: a new kind of street that accommodated many modes of travel, “piggybacked onto the concept of a park and a sewer system,” Allen said.

The parkway was also one of the three major 19th-century innovations passed into the 20th century, Allen said. The others? Public parks, a new kind of public space that was empty, free and open to suggestion, and the planned garden suburb, Olmsted’s attempt to combine the best aspects of rural life in New England with urban life.

“[Olmsted’s] own education was unorthodox,” said Frederick Steiner, dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin and a speaker at the event. “But his singular brilliance and scope of accomplishments are worthy of this [endowed chair].”

“[Olmsted’s] own education was unorthodox,” said Frederick Steiner, dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin and a speaker at the event. “But his singular brilliance and scope of accomplishments are worthy of this [endowed chair].”

CEE’s new Frederick Law Olmsted Chair is made possible through a gift from Jenny and Mike Messner, BSCE ’76. Their vision is for the teacher and researcher selected for the position to instill in their students—and advance through their academic pursuits—Olmsted’s concern for engineering urban spaces that have long-term public benefits.

“Human well-being should serve as the north star on our trek toward sustainability,” said Howard Frumkin, another speaker and dean of the School of Public Health at the University of Washington.

Frumkin said that means designing the built environment to give people what studies have shown makes them happy: clean air, quiet, short commutes, contact with nature, beauty, and “third places”—areas outside of home and work where people can go to be social and enjoy life.

Health is also a piece of that well-being, according to Richard Jackson, chair of Environmental Health Sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles, Fielding School of Public Health. He noted that a 20-year-old’s lung function is a good predictor of how long he or she will live. Likewise, how good an area’s parks are can predict how long people in that area will live.

“If you want people to walk, you have to give them a place they want to walk,” Jackson said.

Of course, it requires public investment and political will to change cities’ approaches to streets, parks and other parts of the urban landscape.

Any bold idea that transforms how cities are using land is bound to be controversial, according to Diane Davis, a Harvard professor of Urbanism and Development. And since cities are constantly changing, the politics of sustainability is also always shifting, she said. So it comes down to leadership.

“Mayors are key players in transforming the urban landscape,” Davis said in her presentation. But designers have to help. They need to be able to think like politicians and help the politicians think technically.

Congress for the New Urbanism’s incoming President and CEO Lynn Richards said those designers and politicians need to think in terms of building infrastructure that meets multiple needs. Cities can’t just spend billions of dollars installing pipes to handle storm water. Those projects need to have other benefits for the community as well, she said.

Congress for the New Urbanism’s incoming President and CEO Lynn Richards said those designers and politicians need to think in terms of building infrastructure that meets multiple needs. Cities can’t just spend billions of dollars installing pipes to handle storm water. Those projects need to have other benefits for the community as well, she said.

In cities where no land remains to create new green space, maybe that means thinking about using public projects to connect existing parks across a region, Richards said, drawing parallels with Olmsted’s linear parks. Maybe it means making our streets places for people rather than just cars, she said, and making our built environment feel more like parks.

Some communities are starting to experiment with those kinds of ideas, turning urban roads back into something resembling the parkways Olmsted built to accommodate all kinds of transportation modes.

The term these days is “complete streets,” which speaker Elizabeth Macdonald defined as providing for multiple forms of movement and gathering while also providing for urban greening.

Macdonald, an associate professor of Urban Design at the University of California, Berkeley, said it’s possible for more communities to build urban parkways like Olmsted did in New York and elsewhere.

“No [user] gets everything [they want], but everyone gets a lot,” Macdonald said.

Visit the Olmsted Chair Search website.